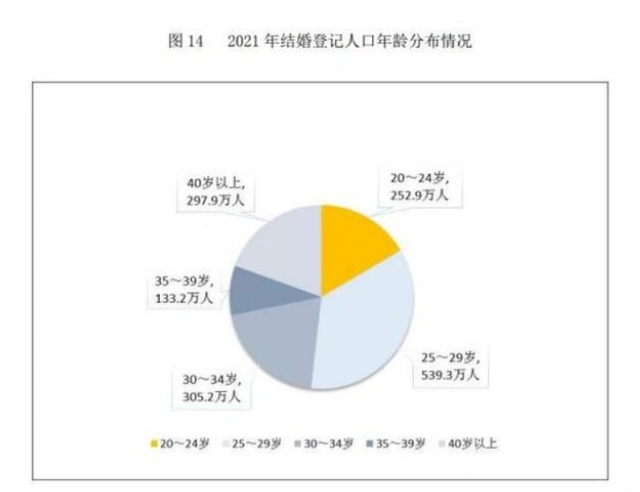

The number of marriages has dropped below 8 million for the first time, with nearly half of those getting married over 30 years old!

According to the “2021 Statistical Bulletin on the Development of Civil Affairs” recently released by the Ministry of Civil Affairs, there were a total of 4,372 marriage registration institutions and venues across the country in 2021, including 1,069 marriage registration institutions. A total of 7.643 million couples legally registered for marriage throughout the year, a decrease of 6.1% compared to the previous year. The marriage rate was 5.4 per thousand, a decrease of 0.4 per thousand compared to the previous year. A total of 2.839 million couples legally processed divorce procedures, a decrease of 34.6% compared to the previous year.

Why aren’t young people getting married and having children nowadays?

It’s not that they are all indulging in self-expression, but that there is a group of people who want to get married and start a family but can’t.

This group includes not only rural unmarried men of advanced age and urban unmarried women of advanced age, but also many highly educated girls in county towns – the so-called “leftover women” in the county town’s public sector, such as teachers, doctors, nurses, and female employees of other government agencies.

Some people may not believe it: I’ve heard that in county towns, there are usually more men than women. As long as girls know to run home when it rains and can “steam buns”, there will be people vying for them. These girls can get into the public sector and stand out in both written tests and interviews, which shows that they are not lacking in appearance or ability. How could they not find a partner?

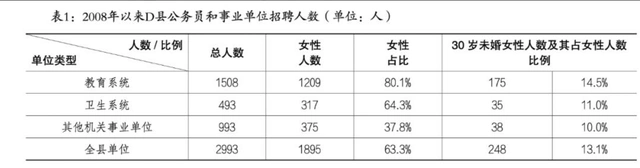

Let’s look at a set of data. This is the number of people recruited by the public sector in a certain county town since 2008, with women accounting for 63.3%, significantly higher than men. Especially in the education system, 80% are girls.

Why? It’s not because of favoritism. It’s because our girls are just too excellent! According to data released by the Ministry of Education, the number of female college students has been surpassing that of male students for many consecutive years. And public sector jobs usually have educational requirements, so it’s not surprising that girls lead the way into the public sector.

However, this has led to a problem. Public sector girls work five days a week, and the circle they interact with is mostly related to work. There are more girls and fewer boys, making it difficult to find a partner. Moreover, as we all know, in most cases, as long as a boy can carry the rice, flour, and oil provided by his public sector employer, he will be a favorite of mothers-in-law and a sought-after matchmaker’s choice. As a result, there are only a large number of unmarried girls and a small number of married men in the public sector.

Since public sector boys are so sought-after, why aren’t public sector girls?

Of course, they are!

But as the saying goes, “When you marry a man, you marry his clothes and food.” Public sector girls have stable jobs and don’t have to worry about clothes and food. Moreover, they have high education levels and a broad knowledge base, so they have higher expectations in marriage. Journalists have found that for these girls, whether their future partners have a car or a house is not the most important thing. What matters is having common topics, similar values, and comparable cognitive levels, and being able to have meaningful conversations. If they can’t get along, they would rather not get married.

At the same time, young men with ideals and aspirations outside the public sector have mostly gone to first- and second-tier cities to seek their fortunes, leaving very few in county towns. Those who remain mostly have lower education levels and work in nearby cement or chemical factories, with unstable jobs and average incomes.

Not only do the public sector girls themselves feel that they are not a good match, but local matchmakers also rarely force a match between public sector girls and young men working in county towns. Here comes the classic theory of mate selection gradient! The best A men marry B women, B men marry C women, C men marry D women, and the remaining D men and the best A women stand in place singing “Single Love Song”. Public sector unmarried women of advanced age in county towns are the remaining high-quality A women.

So, is there no solution? Not really.

In fact, the United Kingdom faced the phenomenon of “female dominance” in higher education earlier than us. In the 1860s, the University of Cambridge in the UK broke the ice by admitting female students. Soon after, other universities followed suit. By 1997, the number of female students in the UK had soared, and by 2008, they accounted for 60% of the total student population, far exceeding the number of male students. However, the marriage rate in the UK did not show any significant fluctuations during this period.

Why are highly educated British girls willing to “marry down” to less educated British boys? Is it because they are all brave for love and disregard the opinions of others?

No, the truth is that as the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution, the UK recognized the importance of vocational and technical education as early as the 1980s. If children couldn’t get into university, it didn’t matter; they were immediately sent to vocational education, and the government provided substantial subsidies. The construction cost of a single vocational college’s internship factory was as high as 2 million pounds per year.

Moreover, the UK was the first to introduce the vocational qualification certificate system, encouraging students to level up.

After graduation, blue-collar workers with technical skills, armed with vocational qualification certificates, could find jobs that were just as respectable and well-paid as those of university graduates. Thus, they were qualified to court university girls in the same coffee shop.

It was only in the last decade or so, when the UK’s industry declined, that their marriage rate began to fall year after year.

Whether you call it a coincidence or a cause-and-effect relationship, in the end, it’s still the economic base that determines the superstructure.

Entering China

Entering China